As promised, here is the first of two reviews of Floyd Landis', Positively False: The Real Story of How I Won the Tour de France. This review was written by my wife, Ellen Finger, who hijacked the book when it arrived fresh from the publicity staff at Simon & Schuster. Another review, by me, will follow though it's clear that I have my work cut out for me trying to keep up with my wife. Additionally, I'm still awaiting word from the Landis camp on his availability for an interview when he comes to Lancaster next week. Hopefully things can be worked out so that more dispatches about this interesting case can be written.

Anyway, here is the first of a series of who-knows-how-many stories from the Finger Family on Landis Avenue in Lancaster, Pa.

Review: Positively False by Ellen Finger

About 10 years ago my future husband took me to downtown Lancaster to watch a professional bike race. I had never enjoyed riding my bicycle as a child. In fact, the first time my dad insisted I try to ride my pink, banana-seat bike without the training wheels I rode right into the back of a parked pick-up truck. Thus started my distaste for cycling. So when John insisted we watch the pros ride through our little city, I reluctantly agreed.

About 10 years ago my future husband took me to downtown Lancaster to watch a professional bike race. I had never enjoyed riding my bicycle as a child. In fact, the first time my dad insisted I try to ride my pink, banana-seat bike without the training wheels I rode right into the back of a parked pick-up truck. Thus started my distaste for cycling. So when John insisted we watch the pros ride through our little city, I reluctantly agreed.

Watching the race from near the top of the Brunswick building on the corner of Queen and Chestnut streets, I got a taste of what attracts athletes to pro cycling – fearlessness, speed, risk, and a fierce competitive spirit. Although I don’t participate in activities unless I’ve made sure to control variables that pose risk, and have never enjoyed or succeeded at endeavors involving speed, I can relate to the competitive nature that bike jockeys need to possess to win. I like to win – or more accurately, I hate losing.

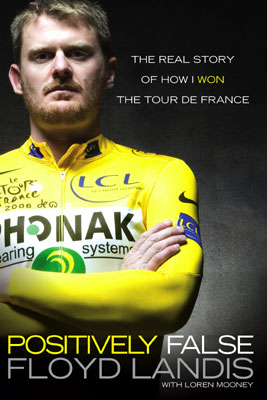

Which might explain why I was drawn to the copy of Floyd Landis’ book Positively False: The Real Story of How I Won the Tour de France that my husband received in the mail from the publisher a few days before its release date. All I knew about the man from Lancaster County (my home, too) was that he won the Tour de France last year after an amazing comeback, and then was accused of doping during the Tour. From the pictures of the back and front covers I could see that this man with the intense eyes and triumphant scowl hated losing, too.

Three days ago I sat down to thumb through the 306-page memoir and look at the pictures of Floyd’s childhood. Though I grew up only about ten miles from the Landis family, my suburban sprawl neighborhood close to the Park City mall was really a world away from Floyd’s conservative Mennonite home in Farmersville. Heck, I had never even heard of Farmersville until the summer of 2006.

What started out as a casual glance at his book became an almost obsessive need to read and learn more about the man and his mission. Between diaper changes, yardwork, grocery shopping, and other responsibilities of a wife and mother, I did nothing but read Floyd’s book. Obviously it’s not because of an interest in cycling, but I do enjoy sports and nonfiction books. I initially was curious to find connections between my life and upbringing in Lancaster and Floyd’s. Eventually, though, I realized I was reading to find the truth. I, like many people, assumed that someone whose urine test reveals a level of testosterone that is significantly elevated is definitely a cheater. I follow rules, always have. Cheaters and liars, especially ones who get paid a lot of money for playing sports, make me sick. But something about this man, this brash, outspoken man who still looks like most of the Mennonite and Amish boys I see occasionally when I drive through eastern Lancaster County, made me want to look beyond the seemingly logical conclusion (his miraculous performance in Stage 17 of the Tour had to have been due to performance-enhancing drugs, right?) to see if there was more to the story.

Before I could really delve into the myriad of scientific detail, political absurdity, and tales of athletic glory, I had to admit something to myself. One thing that has always bothered me about men who spend their lives playing games is that it ultimately seems like an incredibly selfish pursuit. The older I get the more I feel like my life is not my own. I am constantly thinking about working a full-time job for someone, taking care of someone, cleaning up after someone, or saving money to buy food, clothes, or diapers for someone else. Floyd even admits in his book that he “put training first, even before (his) family. When you want to win, you eat, drink, sleep and breathe cycling.” Well, I want to win when I play, too, but who has time for games? I know, I know, professional cycling isn’t just a sport, it’s a job. And it’s a well-paying one for athletes like Landis, at least after many years of toiling as an amateur and then an underpaid professional domestique (servant to a cycling champion like Lance Armstrong). But, I just can’t understand the need of some men to spend months away from loved ones and pass their time alternating between grueling training and zombie-like resting. Maybe I’m jealous of their apparent luxuries, maybe I will never realize my full potential as in individual, or maybe I’m just a grown-up.

As I read I realized that I believe Floyd Landis. Not only has the man spent almost all of his money trying to mount a defense against doping charges and has made his fight very public, as opposed to those swollen (by that I’m referring to their synthetically-enhanced muscles AND egos) arrogant baseball players testifying before Congress with apparent memory problems, but also he has brought to light the extremely screwed-up anti-doping agencies that exist here in the U.S. and around the world. I’m not sure how much of our taxpayers’ money and legislators’ time should be spent revamping an obviously corrupt system, but something needs to be done. If our government funds the USADA (America’s relatively young sports anti-doping agency) it does so without really having any idea how the organization operates.

And if they do, Congress is guilty, too. But I suspect that the same kinds of minds that wrote and sold the brilliantly-titled law No Child Left Behind (which might be leading to better performance on hardly standardized tests while dampening a desire for real learning and teaching in our increasingly stressed out schools) also championed the anti-drug movement that supposedly is trying to clean up sports. The problem is that most senators and representatives never have time to really read about or follow up on the intricacies of the legislation they pass. They hear convincing sound bites (who wouldn’t want to rid professional sports of cheaters and druggies and who WOULD want to leave a child behind?) and hope for the best. But Landis reveals in great detail how duped – not doped – we all are about the injustices these government-sponsored agencies have quietly inflicted on athletes, particularly in cycling. I was shocked and appalled to learn that the people who test the urine of pro athletes, the people who bring doping charges against athletes, the people who prosecute accused athletes, and the people who judge the fates of these same athletes – they all work for the same agencies. How un-American is that? Even my fourth graders know that there must be a system of checks and balances to ensure that justice prevails.

And if they do, Congress is guilty, too. But I suspect that the same kinds of minds that wrote and sold the brilliantly-titled law No Child Left Behind (which might be leading to better performance on hardly standardized tests while dampening a desire for real learning and teaching in our increasingly stressed out schools) also championed the anti-drug movement that supposedly is trying to clean up sports. The problem is that most senators and representatives never have time to really read about or follow up on the intricacies of the legislation they pass. They hear convincing sound bites (who wouldn’t want to rid professional sports of cheaters and druggies and who WOULD want to leave a child behind?) and hope for the best. But Landis reveals in great detail how duped – not doped – we all are about the injustices these government-sponsored agencies have quietly inflicted on athletes, particularly in cycling. I was shocked and appalled to learn that the people who test the urine of pro athletes, the people who bring doping charges against athletes, the people who prosecute accused athletes, and the people who judge the fates of these same athletes – they all work for the same agencies. How un-American is that? Even my fourth graders know that there must be a system of checks and balances to ensure that justice prevails.

So there it is. I really don’t care about cycling. The ridiculous dichotomy of rigorous training coupled with slovenly relaxation, as well as the complicated team dynamics of cycling, and the unwritten rules of the peloton that result in good athletes having to sacrifice their own efforts to protect the diva-like team leader are foreign concepts to me.

But I desire for truth and for justice. Good people should win. Hard work should be rewarded. Incompetence (as so obviously displayed by French drug labs) and corruption (the USADA and WADA come to mind) and selfishness (UCI is guilty here) should have no place in our society, but they do. Floyd Landis won the Tour de France. I hope he can race again. But mostly I hope finds some satisfaction knowing that his most important and biggest uphill climb will be to bring awareness and hopefully, change, to one kind of injustice plaguing America today. Despite what his parents thought, and may still think, about the perils of a life spent outside of their pious community, I hope they know that their boy still knows right from wrong.